The reshaping of the global economy: Riding the waves of change

As China’s property market tanks, countless families find themselves entangled in payment problems. Many struggle to make mortgage payments, often on properties they have yet to receive. Others are stuck, like university administrator Nelson Lau, 32, paying for a new apartment but finding it hard to sell his existing property amid falling housing prices.

“We’ve had to cut back on groceries,’’ said the father of one from Guangzhou. “Some days, we feel like we are living pay cheque to pay cheque…it really keeps me and my wife up at night.”

In India, call centres are having to confront the dilemma posed by generative artificial intelligence (AI). Although AI helps improve business efficiency and customer experience, it has also led to Indian entrepreneur Suumit Shah axeing staff from his e-commerce site dukaan.com.

“We had to lay off 90 per cent of our support team because of this AI chatbot,” he tweeted earlier this year. “Tough? Yes. Necessary? Absolutely.”

It’s a similar situation in the Philippines, where in May, Senator Imee Marcos called for an inquiry, citing research estimating that digital automation could make 1.1 million jobs in the Philippines obsolete by 2028. “AI is developing faster than most people can comprehend, and is threatening to take away jobs and turn employment growth upside down,” she said.

But it is not all gloom for India and the Philippines. The two countries, together with Thailand, Vietnam and Indonesia, are getting new investments from the US and Europe as supply chains get reconfigured.

After reaping the benefits of globalisation and ultra-low interest rates for more than a decade, Asia’s economies must now confront a very different world.

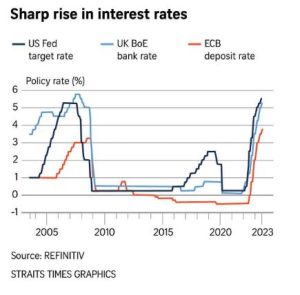

A series of shocks and disruptions have occurred over recent years that few foresaw. Among them, rifts along multiple axes between China and the United States; a global pandemic; the reshaping of supply chains; the resurgence of inflation, which triggered draconian and rapid tightening of monetary policies; more frequent climate-related disasters; a possibly prolonged economic slowdown in China and, most recently, the acceleration of automation, driven by the rapid adoption of AI.

Taken together, these developments are causing tectonic shifts in the global economy, and for Asia a source of both threats and opportunities, but also great uncertainty.

At least over the next year, the outlook is clouded by a likely slowdown in the global economy. In the July update on its World Economic Outlook, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) projects that global gross domestic product (GDP) growth will fall from 3.5 per cent in 2022 to 3.0 per cent in both 2023 and 2024. By historical standards, this would be markedly weaker than the average of 3.6 per cent growth during 2010-2020.

While a global recession seems unlikely, especially with United States growth remaining robust, it can’t be ruled out, given that monetary tightening – which is still not over – takes about 12 to 18 months to fully impact the real economy, and the economic slowdown in China. And even though inflation has come down globally this year, it could remain a wild card. Food prices have surged in recent months in the wake of Russia’s refusal in July to renew a deal which allowed ships to transport grain from Ukraine across the Black Sea and India’s curbs on rice exports. Meanwhile, recent announcements of oil supply cuts by Saudi Arabia and Russia are pushing fuel prices upwards.

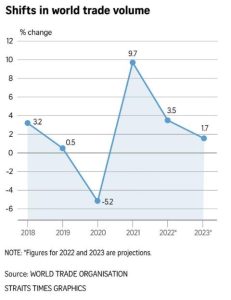

The growth of world trade – on which Asia’s economies are highly dependent – is slowing even faster than that of GDP. The World Trade Organisation (WTO) estimates that by volume, goods trade will rise by only 1.7 per cent in 2023, compared with an average of 2.6 per cent in the 12 years since it collapsed during the global financial crisis of 2008.

Politically driven

The slowdown is partly the result of trade being driven more by politics than economic fundamentals and trade rules, resulting in bans on exports of various commodities and technologies, rising import protectionism – including in the US and Europe – and more localisation of supply chains.

But economic forces have also played a part. As Mr David Lubin, the head of emerging markets economics at Citigroup, points out, besides tepid GDP growth, which automatically translates into slower trade, the world is still suffering from a “trade hangover” after a pandemic-era surge when people splurged on goods, especially in advanced economies.

They have now switched their spending to services, which are less traded than goods. Slower growth in China has also slashed the demand for both commodities – for many of which China is the world’s biggest importer – and consumer goods.

The slowdown in China, which alone accounts for almost half of Asia’s GDP, could be a major disruption for the region, especially if it is prolonged.

Its causes are mainly domestic. China’s real estate sector, which accounts for 25 to 30 per cent of its economy, is in crisis. Property prices, which are the most expensive in the world relative to incomes, are falling, together with sales volumes. Consumers are holding back from spending because many are paying down their debts and are faced with deflation, which discourages consumption.

Saddled with excess capacity, many Chinese companies are reluctant to invest. With exports weak because of slowing global growth and trade restrictions, a fiscal stimulus seems the only remaining option. But that, too, has constraints: Local governments which depend on land sales for most of their revenue are too cash-strapped to spend, and Beijing has been wary of launching a broad-based stimulus as in 2008 because of already high levels of public debt, falling returns to additional injections of capital and the overhang of excess property.

Stimulus may take the form of targeted measures aimed at providing relief to distressed sectors, but that will, at best, only stabilise growth at a historically low level.

A secular slowdown

Some economists fear that China’s slowdown could be secular. Dr Adam Posen, president of the Peterson Institute for International Economics, describes it as “economic long Covid”.

Mr Richard Koo of the Nomura Research Institute in Tokyo points out in a recent research report that like Japan in the early 1990s, China faces the prospect of a “balance sheet recession” whereby consumers and business focus on repairing their balance sheets rather than spending or investing. If this happens on a large scale, the economy would struggle to recover, possibly for years.

In keeping with an increasing inward orientation, China’s government wants to shift the main driver of its economic growth from investment to household consumption, which at barely 40 per cent of GDP, is among the lowest in the world.

The economist Michael Pettis of Peking University suggests that shifting to consumption-driven growth would require a massive transfer of resources, to the tune of at least 10 percentage points of GDP, from the state sector to the household sector, through wage increases for workers, better benefits and tax transfers.

That, in turn, would imply “a huge shift in the relative political power of different sectors of the economy and a major transformation in the country’s relevant social, political, and economic institutions”, he points out in a Carnegie Endowment for International Peace article earlier this year. That is not impossible, but would be politically difficult to pull off, and will happen slowly, if at all.

Besides its domestic imbalances, China’s economy is being buffeted by geopolitical rifts, especially with the US, which also has profound implications for Asia.

Since 2018, China has been subject to US tariffs on a wide range of products and industries. It is also facing restrictions on technology transfers, including high-end semiconductors and related equipment. In addition, the US and Europe have resorted to policies of “de-risking” in trade, purportedly to avoid excessive dependence on any one country for key imports. China, which is the source of many such imports, is the country most affected by this. De-risking has involved policies that encourage “re-shoring” – the relocation of production back home – as well as “friend shoring” whereby some production is shifted to “politically aligned” countries.

Re-shoring has been accompanied by a rise of protectionism – for example, through policies that favour domestic producers of climate-related products and services as well as semiconductors in both the US and Europe. These policies will disadvantage Asian producers, which can produce these products more competitively.

But some Asian countries also stand to benefit from the diversion of production from China. This is already evident in trade flows. The World Bank points out, for instance, that while China experienced more than a 4 percentage point drop in its share of US imports during 2018-2022, with the largest decline in the electronics industry, Asean economies such as Vietnam, Thailand, and Indonesia increased their share of US imports, also mainly in electronics.

More shifts in production may occur. The latest surveys by US and EU Chambers of Commerce in China indicate a sharp rise in the share of firms that either have begun to, or plan to, relocate investments from China or reduce sourcing of inputs from China.

But Chinese companies are adapting to the reshaping of supply chains. Mr Aaditya Mattoo, the World Bank’s chief economist for East Asia and the Pacific, told The Straits Times that the relationship between many of these companies and those in the rest of Asia is being reconfigured.

Whereas in the past, Asian companies supplied inputs to China, increasingly, Chinese companies are becoming suppliers to Asia. Some are also investing in the region – partly to avoid trade and investment restrictions applied to China as well as regulatory uncertainty at home, and to benefit from preferential trade arrangements such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership.

Accompanying the shifts in supply chains will be changes in the flows of foreign direct investment (FDI). But the extent to which Asia, ex-China, will benefit is unclear. In the April edition of its World Economic Outlook, the IMF estimates that FDI declined by almost 20 per cent in the post-pandemic period from the second quarter of 2020 to the fourth quarter of 2022, but adds that the decline has been uneven across regions.

“Asia became less relevant, both as a source and host of FDI, losing market share vis a vis almost all other regions,” it points out.

The flow of FDI to Asia in strategically important industries such as leading edge semiconductors, certain pharmaceuticals and battery-related technologies started to decline in 2019 and by the last quarter of 2022, Europe got about twice as much of such investment as Asia.

Drawing a distinction between “horizontal” FDI – which refers to foreign firms entering a country to serve local markets – and “vertical” FDI where firms invest to produce inputs for export, the IMF suggests that the latter is more vulnerable to disruption in a fragmenting world – which suggests that Asian component exporters will lose out to countries with large domestic markets.

Over the medium term, the upshot for Asia of both China’s slowdown and the changes in investment flows is likely to be that the growth of Asian exports of finished goods and commodities to China will moderate; a lot of supply chains will move from China to South-east Asia; China’s role as a provider of inputs to the region will grow, together with Chinese FDI; and larger Asian markets outside China, such as India, South Korea and Indonesia, will be favoured as destinations for Western FDI.

New emerging risks

As the de-risking of trade and investment proceeds, new risks could emerge. According to the World Bank, these could include differing approaches to data flows across locations, export restrictions on ultimate destination – for example, to prevent Western exports of sensitive items to Asia from being re-exported to China – as well as import restrictions on ultimate source, to prevent China from circumventing tariffs by routing its exports from elsewhere.

Such politically-driven moves, together with re-shoring and friend-shoring, will both hurt China and lead to higher costs for the US and European companies and consumers. They will also impact Asian supply chains in unpredictable ways.

Another risk is that restrictions on technology flows in particular would impact the sharing of knowledge, which will set back innovation.

Unrelated to developments in trade and investment, many East Asian countries face risks associated with ageing populations. In China, Japan, South Korea, Singapore and Thailand, the share of the working age population is already on the decline. This will impact economic growth, create labour shortages and lead to rising pressures on public finances from higher healthcare and pension costs as well as shrinking tax bases.

Over the coming years, the deployment of automation and AI could mitigate some of the problems related to ageing and slower growth by boosting productivity.

An April 2023 report by Goldman Sachs on the impact of generative AI points out that most workers will be complemented rather than replaced by AI, but there will be variations by territory. It estimates that the proportion of full-time-equivalent employment that is exposed to automation by AI is close to 25 per cent in Singapore, Japan and South Korea, over 20 per cent in Taiwan and Malaysia, 15 per cent in China and Thailand, and 12 per cent in India and Vietnam. “But the higher the exposure, the greater the potential for productivity growth over a 10-year period,” it points out.

But in its 2023 report on World Employment and Social Outlook Trends, the International Labour Organisation (ILO) cautions that AI and other types of automation can have positive effects on productivity only if workers have the education and skills to use them.

Thus, upskilling and reskilling “will be essential to the implementation and diffusion of new technologies as well as the realisation of productivity gains”, which will pose challenges, especially for low- and middle-income countries. In a 2016 report on automation in Asean’s developing economies, the ILO had warned that low wages and skill levels in Cambodia, Indonesia, Thailand and Vietnam will disincentivise workplace automation.

The economics Nobel laureate Mike Spence told The Straits Times that while he’s optimistic about the impact of AI and automation in the long run, it will need changes in the way organisations work, as well as new business models and learning, all of which will take time.

“It’s one thing to have the potential but another thing to have it fully deployed and show up in the way economies function,” he said.

Finally, no analysis of the future of Asia would be complete without accounting for the impact of climate change. The facts here are sobering.

Countless studies have documented the vulnerability of the continent to climate risks, such as rising sea levels, floods and cyclones because of the high density of population and economic activity along the coasts. More than half of the annual losses from natural disasters worldwide occur in East Asia and the Pacific.

The World Bank estimates that without major adaptation efforts, coastal, river and chronic flooding alone could lead to GDP losses of 5 per cent to 20 per cent by 2100 in Indonesia, Vietnam, the Philippines, and China. Most Asian countries are also vulnerable to heatwaves, with negative impacts on health, crop yields, infrastructure and ultimately, liveability, which call for urgent action in areas ranging from developing localised heat action plans to changes in urban design and construction.

Asia has weathered many economic and other crises in the past and yet emerged as the world’s fastest growing and most dynamic region. There is much hope, and hype, about this being the “Asian century”. But in a fracturing world faced with multiple disruptions, the region will need all its capacity for adaptation, resilience and innovation to make such dreams come true.

Source : https://www.straitstimes.com/world/the-reshaping-of-the-global-economy-riding-the-waves-of-change